Diana Chalakova

About

Through AI’s Eyes

The Museum of Science in Boston partnered with the Parsons School of Design in a collaborative course on rapid prototyping for interaction design. I led my team of four in concept ideation, research, info architecture, and prototyping while constantly meeting with the stakeholders and our developer before I led usability testing on the functional high-fidelity prototype in the museum.

Role

UX Design, Web Design, Research

Timeline

Aug – Dec 2025 (4 months)

Tools

Adobe Illustrator

Adobe Photoshop

Adobe InDesign

Midjourney AI

Problem

How might we create and test a high-fidelity prototype that teaches museum visitors about a modern scientific revolution?

The Museum of Science in Boston partnered with the Parsons School of Design in a collaboration that was centered around using their new “Flexible, Accessible Strategies for Timely Digital Exhibit Design” (FAST) table technology. They wanted us to create a high-fidelity prototype and perform in-person usability testing with it to investigate whether they should continue with the technology.

Solution

An interactive game that puts the user in the role of AI identifying objects in a nature scene.

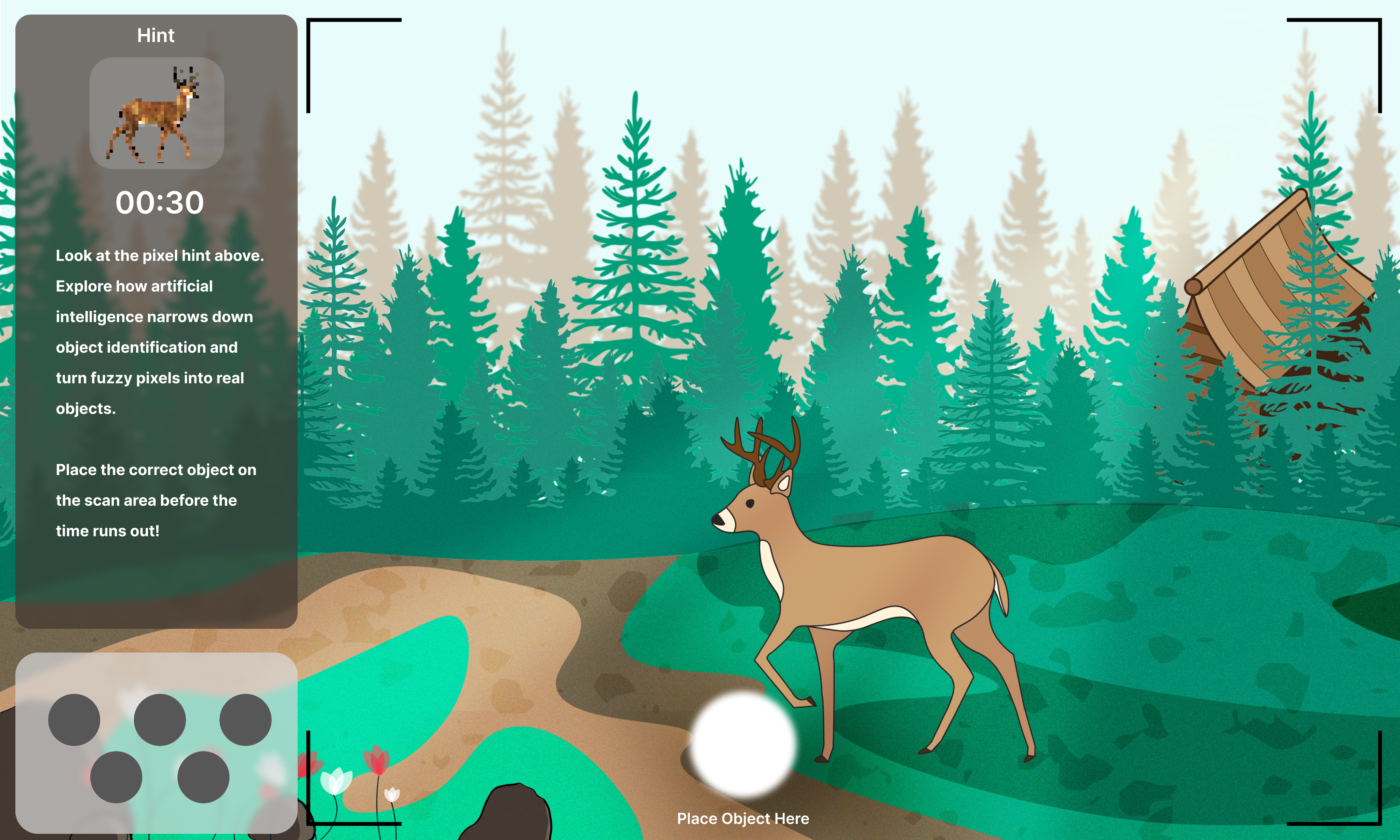

Instead of using verbal prompts, we have visual prompts as pixelated image that slowly become clearer. We wanted to lean into the concept of “productive struggle”, so the system presents a pixelation of one of the five objects and the user has to decide which corresponding object in the scene it is before 30 seconds are up by placing the respective 3D print on the detecting platform, as each object has a unique QR code that the system scans.

Our objective was that by playing, users would learn how hard it can be for AI to identify objects, as AI systems use patterns, colors, and shapes to make educated guesses about what they see. Just like humans, AI can get confused when objects look similar or when clues are vague. The broader message for adults would be about why training data is so important in machine learning. When AI misidentifies objects, it can affect real people – from self-driving cares mistaking shadows for obstacles to photo apps mislabeling faces.

Research

Using simple, unbiased, and objective shapes to test a complex process.

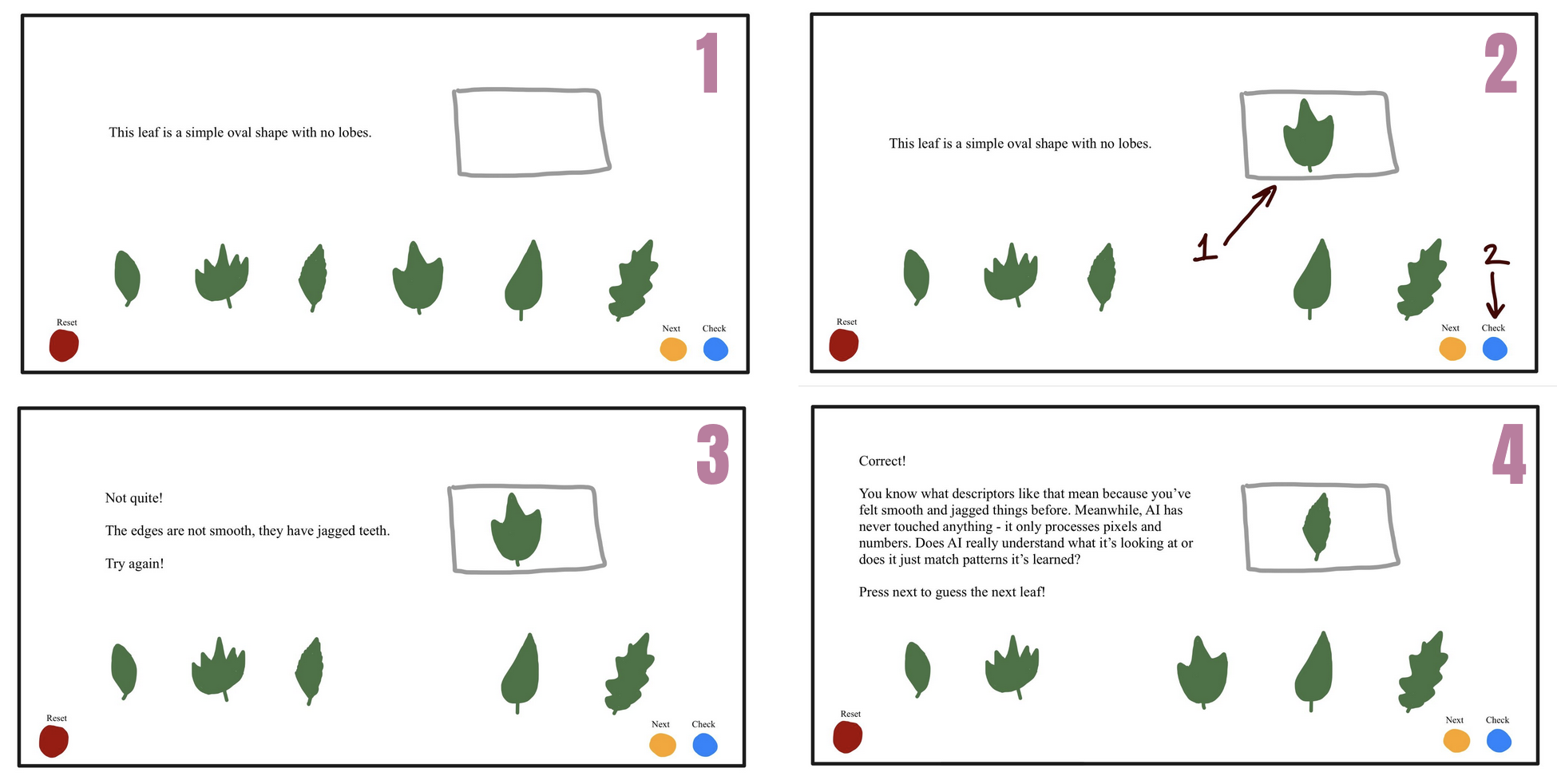

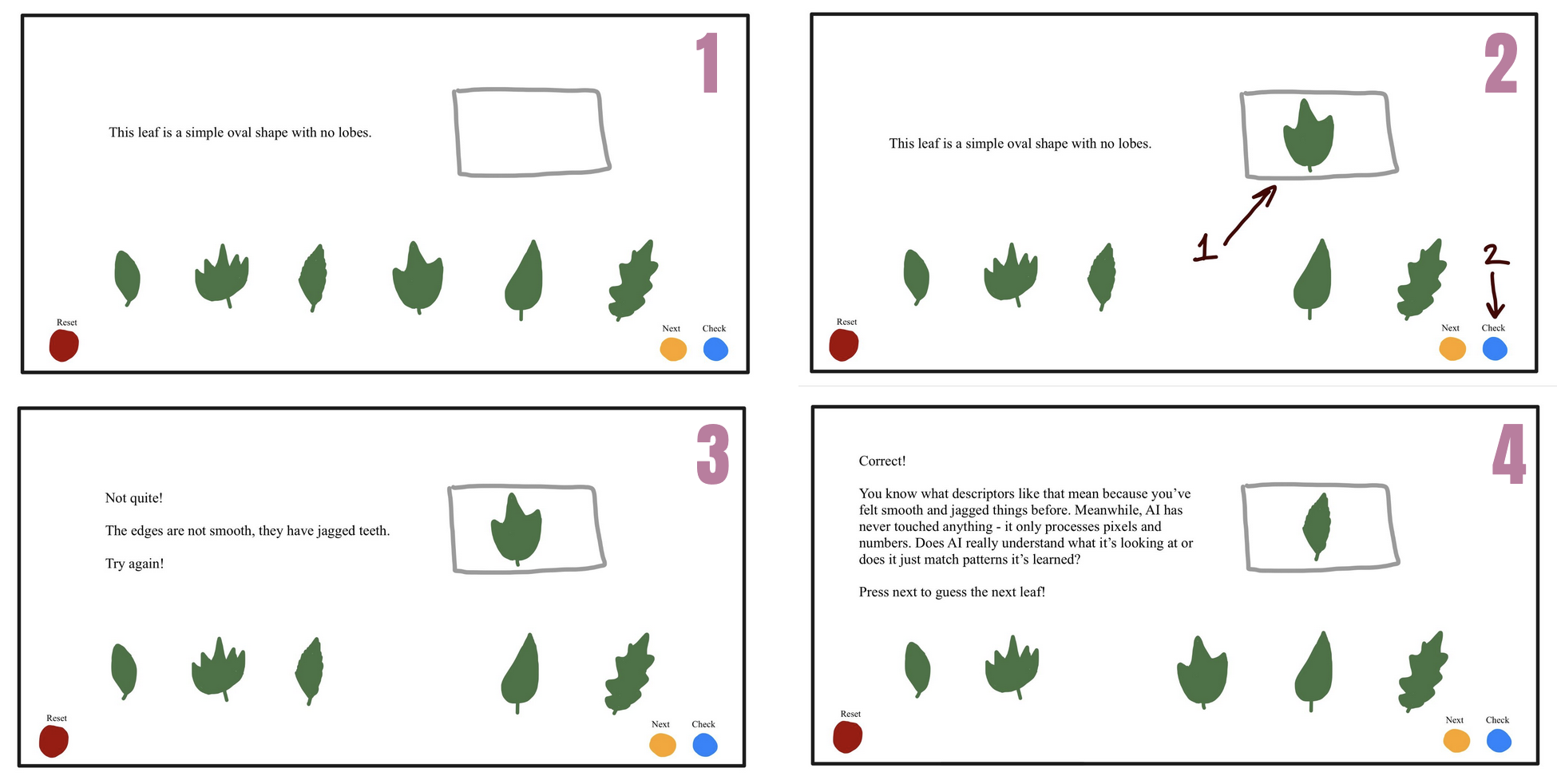

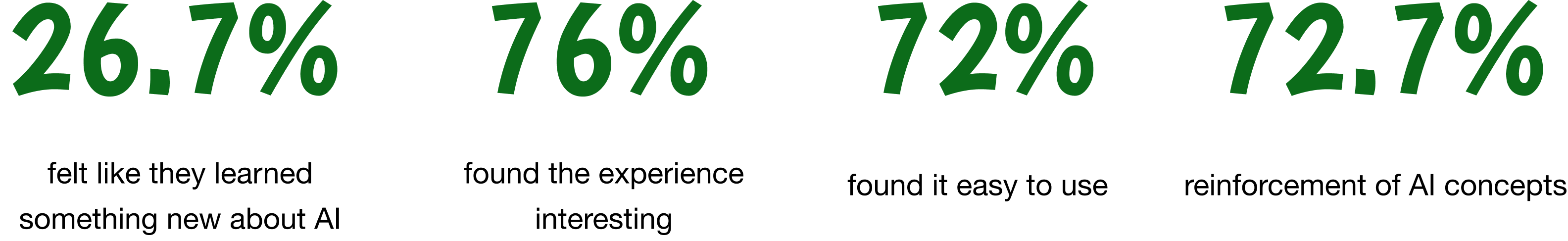

We started our ideation process using leaves as an unbiased and widely understood object. The user would be presented with 6 similar but still different objects, the system would give a very vague prompt, and the user would have to make a guess as to which object it’s referring to. If the user is right, it moves onto the next general prompt. If they are not, the system gives a slightly more specific prompt.

The following is a storyboard that I created to show our stakeholders at the museum what our concept was, which they were very excited about:

We used simple shapes to perform our playtesting with five participants. Participants were instructed to read the prompt and place their object of choice on top of the Apple computer’s logo. Most of them placed possible shapes on the side as a visual aid to help them narrow down their options. Everyone was able to guess the objects during the first two attempts. We discovered that we need to have clear instructions for removing previous objects and that participants fidgeted with blocks like Legos, so we need to make the final 3D print durable.

However, we realized that the written prompts were not centered enough around AI and there was a disconnect between AI object recognition and prompt engineering that was a gap in our concept. Stakeholders also wanted the objects to be all completely different from one another.

Ideation

Using storytelling and visual prompts to create an educational experience.

As a solution to the AI concept disconnect, I proposed that we give the user visual prompts rather than written prompts. This would be similar to how the game Cooking Mama by Square Enix presents to players a pixelated image that slowly depixelatates of the next ingredients that players need to pick before the image becomes clear..

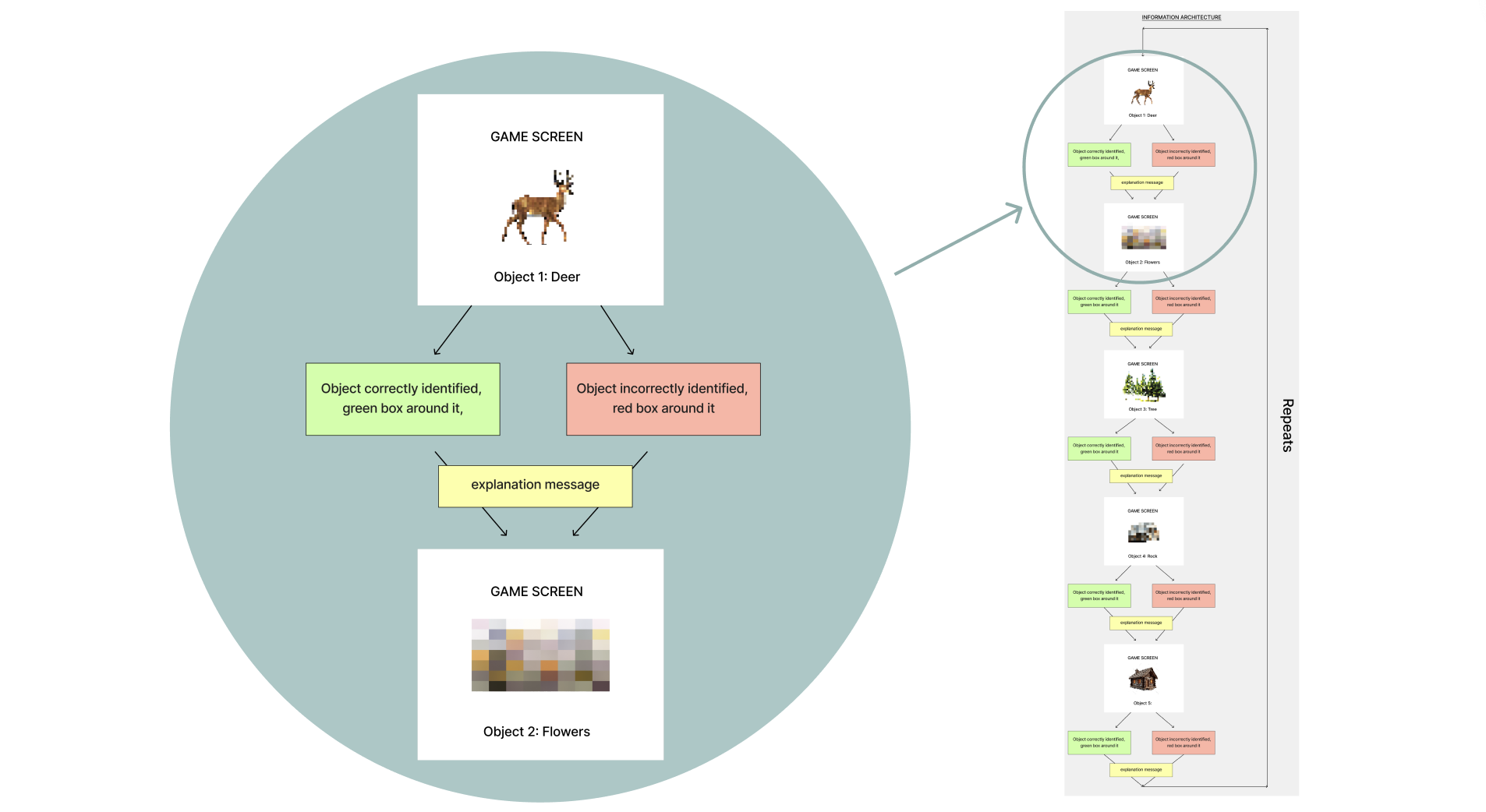

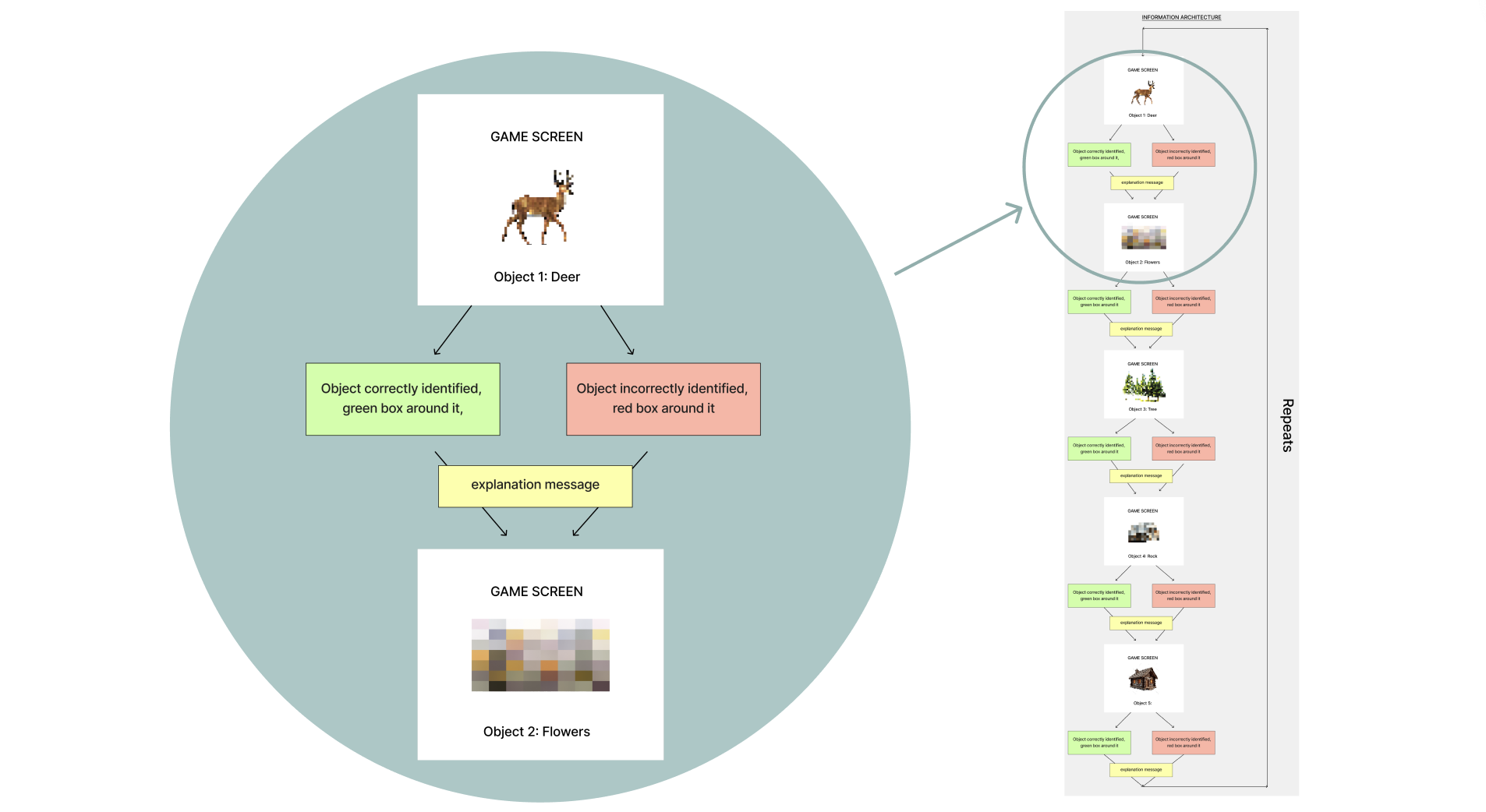

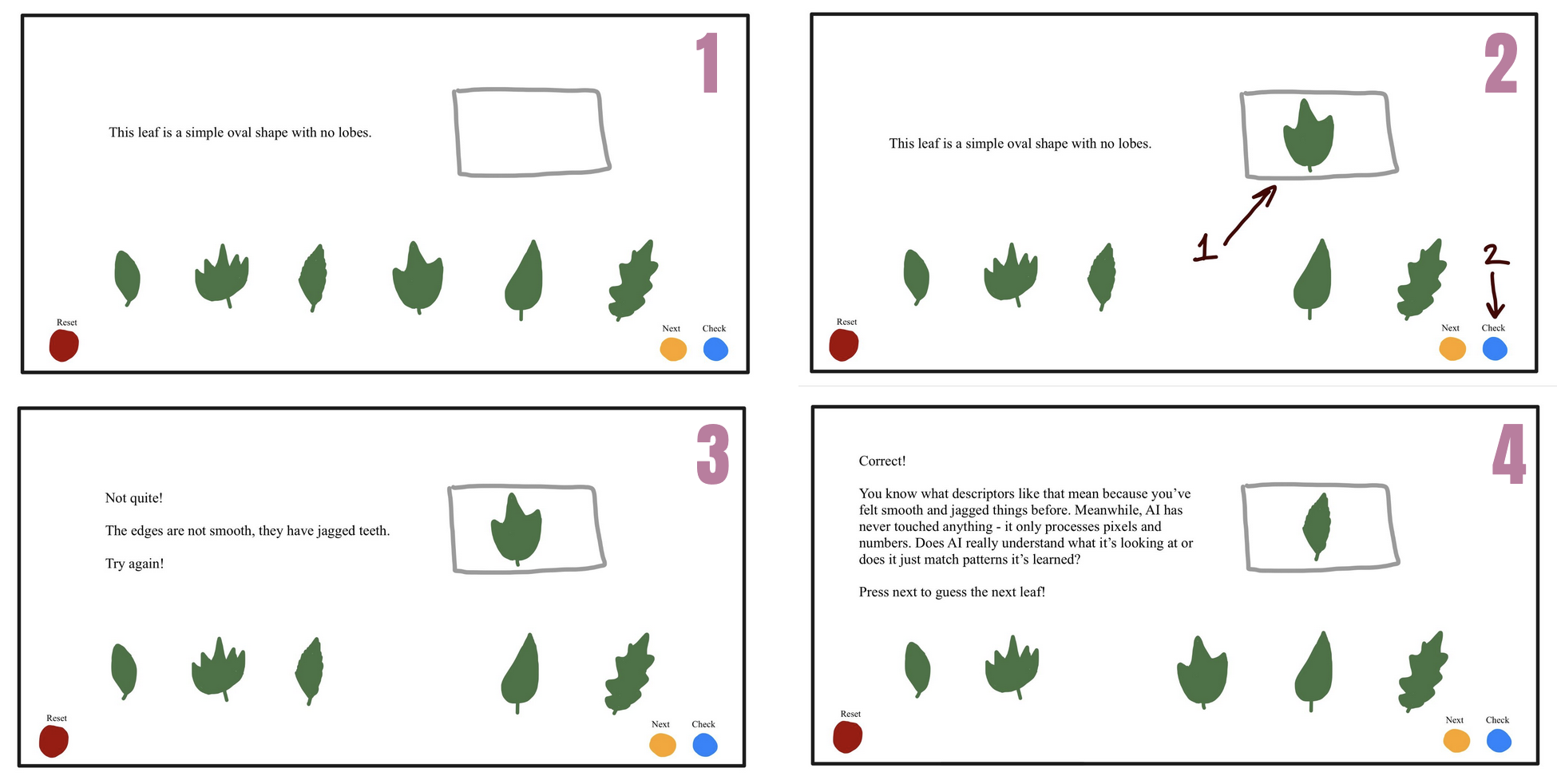

To align with the stakeholder needs of the objects all being different, I proposed that we have the objects live in the same world so we can still tell a story with the experience. The world I suggested which we continue with was a forest scene with the user viewing it through a trail camera, with the objects being a deer, tree, flower, rock, and cabin. The following is the information architecture I created:

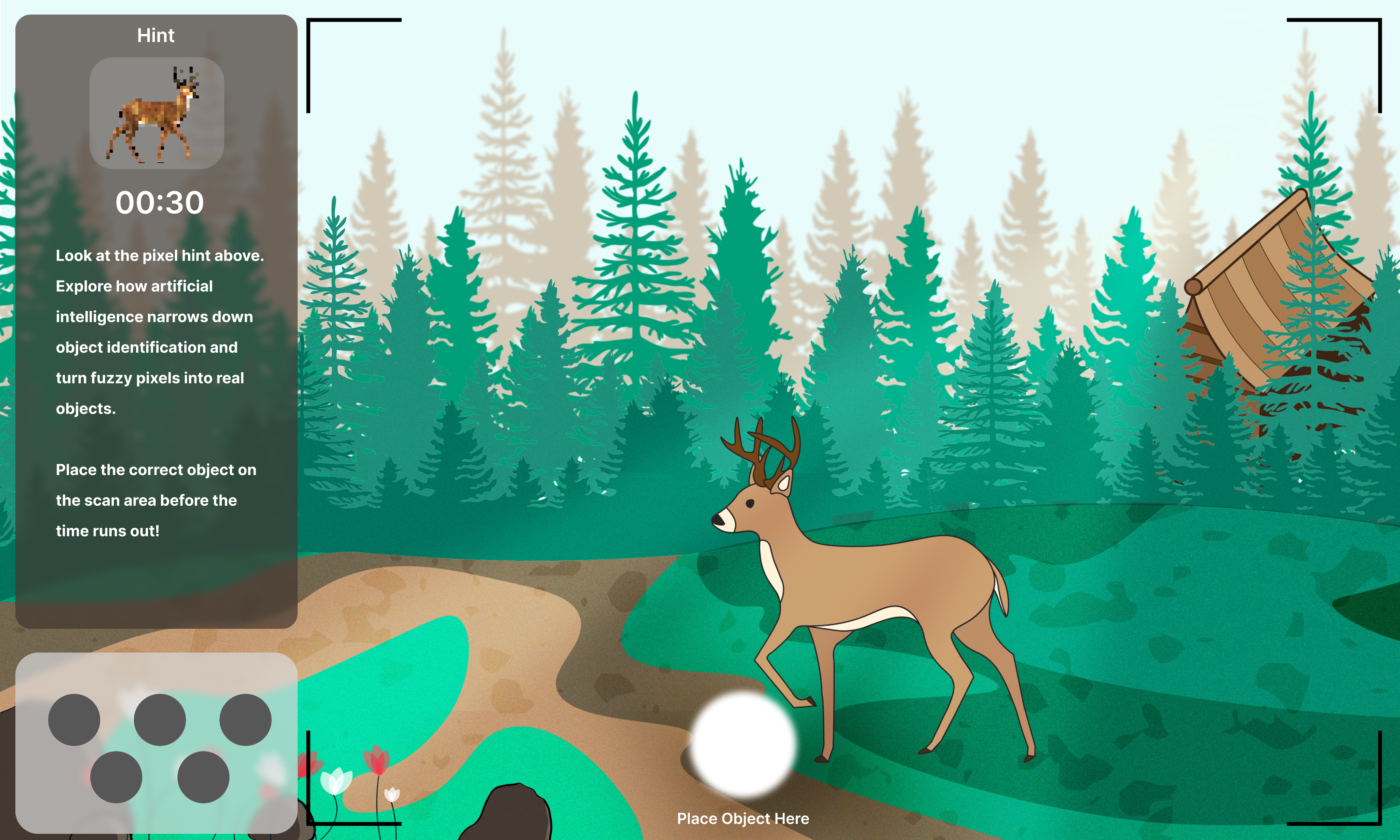

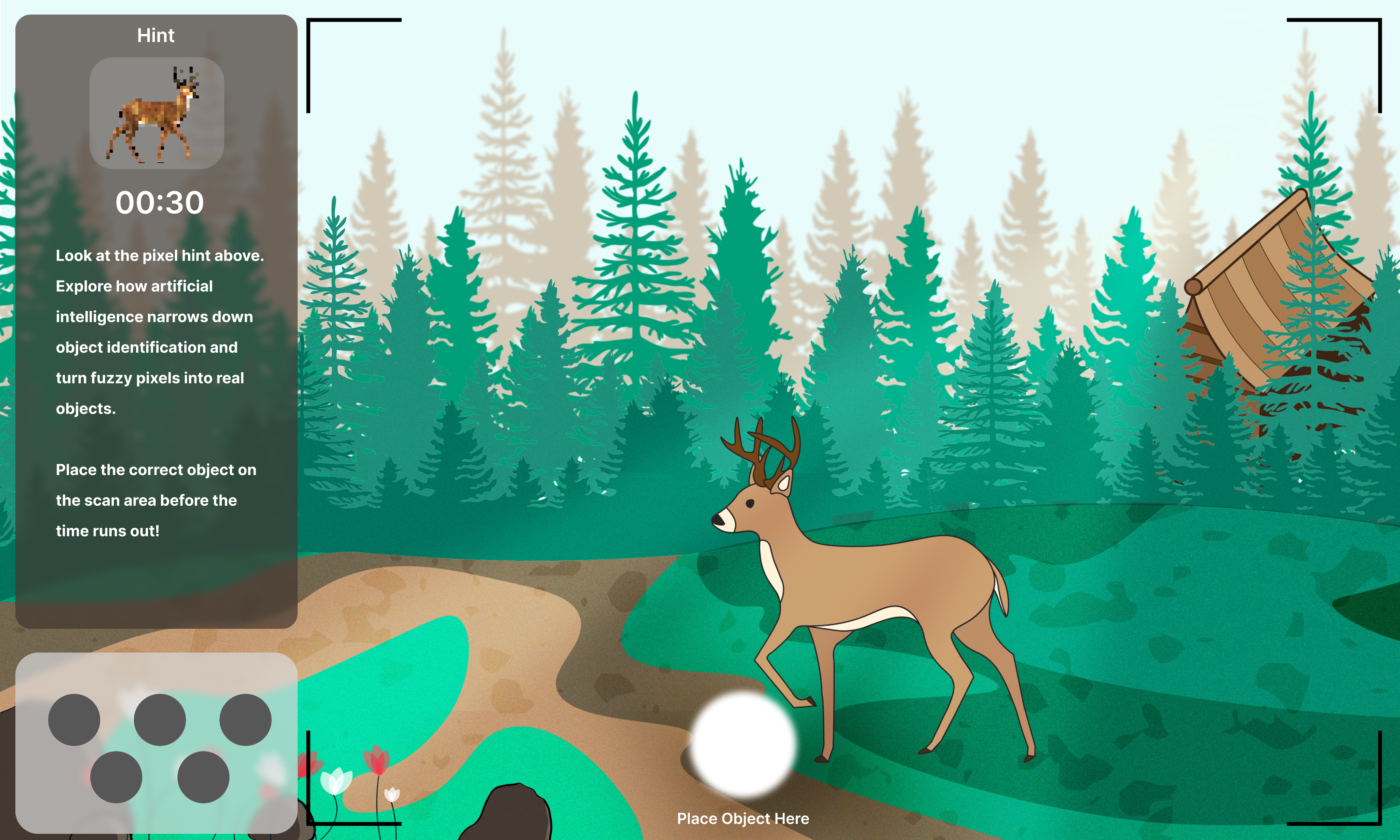

The rest of my teammates each respectively created the visuals assets, worked on the Unity development of it using the template the museum gave us, and created the 3D prints of the objects. I led the planning and creation of the high-fidelity wireframes in Figma for development to work with. I made sure that the camera details were minimal to not be distracting and the different components of the experience were labeled for user ease of understanding.

In the 30 second countdown, the image would come more into focus. The circles at the bottom represent the five different 3D printed objects. Despite the prompt being visual, we felt it was important to still have a written statement about the objective of the experience and connect it to AI.

When the user guesses it right, the object is highlighted in the scene by a green box. If they guess it wrong, it’s a red box. Either way, the explanation of how AI would think about it remains the same, going back to the guessing screen for the next object. The system cycles through them at random, with no end.

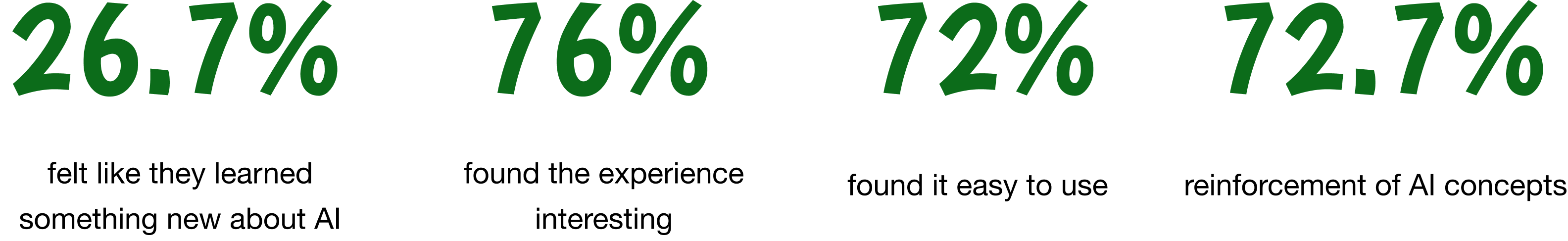

Usability Testing Results

Testing in the Museum of Science with the target audience.

We tested our prototype with 15 users between ages 4 to 65. Data collection methods were focused on one-on-one interviews and observing behavior. We had a team member giving users an onboarding speech that informed them that we will not collect any identifiable characteristics, two team members observing user behavior and encouraging thinking out loud, and other performing post-experience interviews.

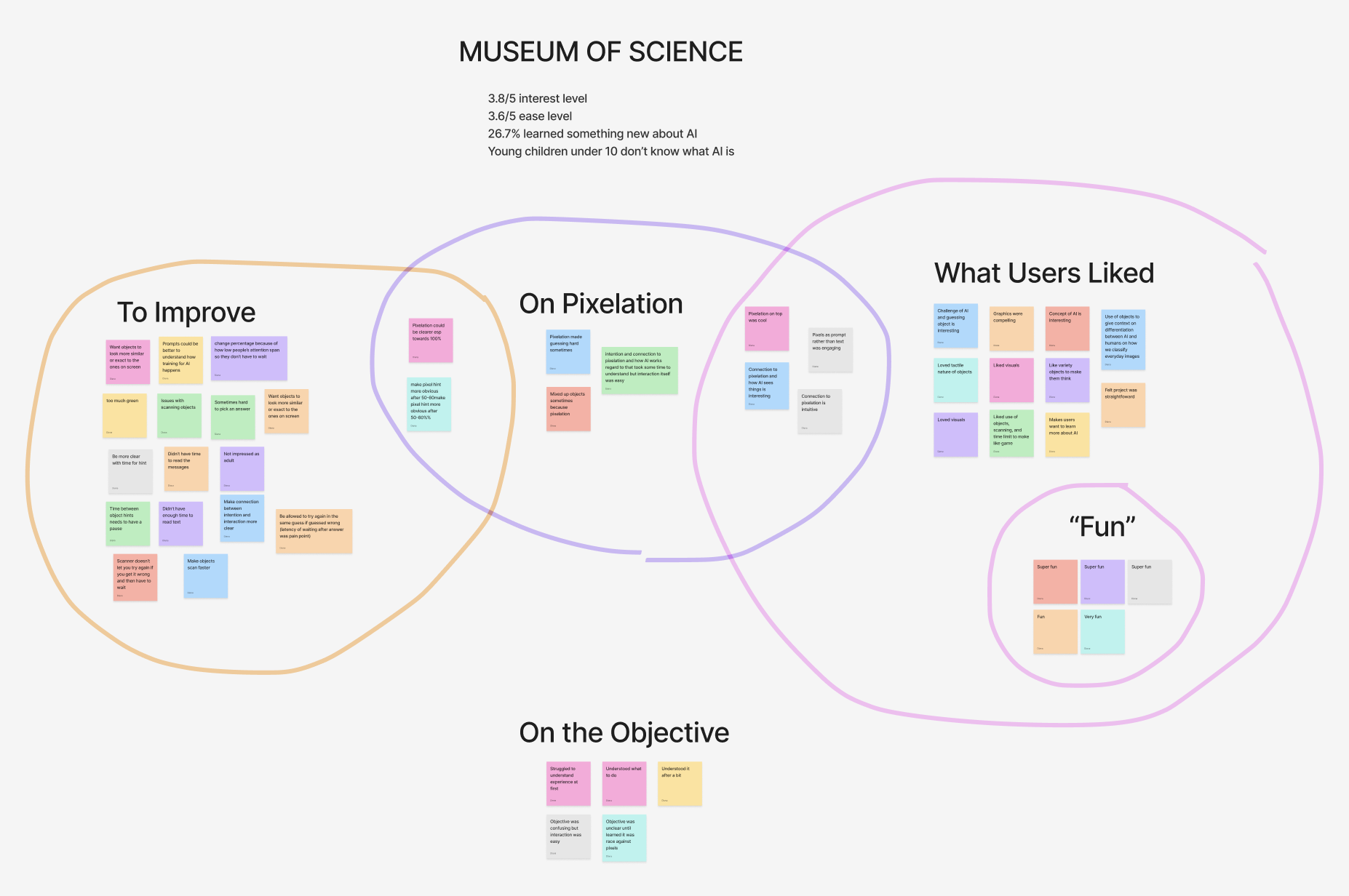

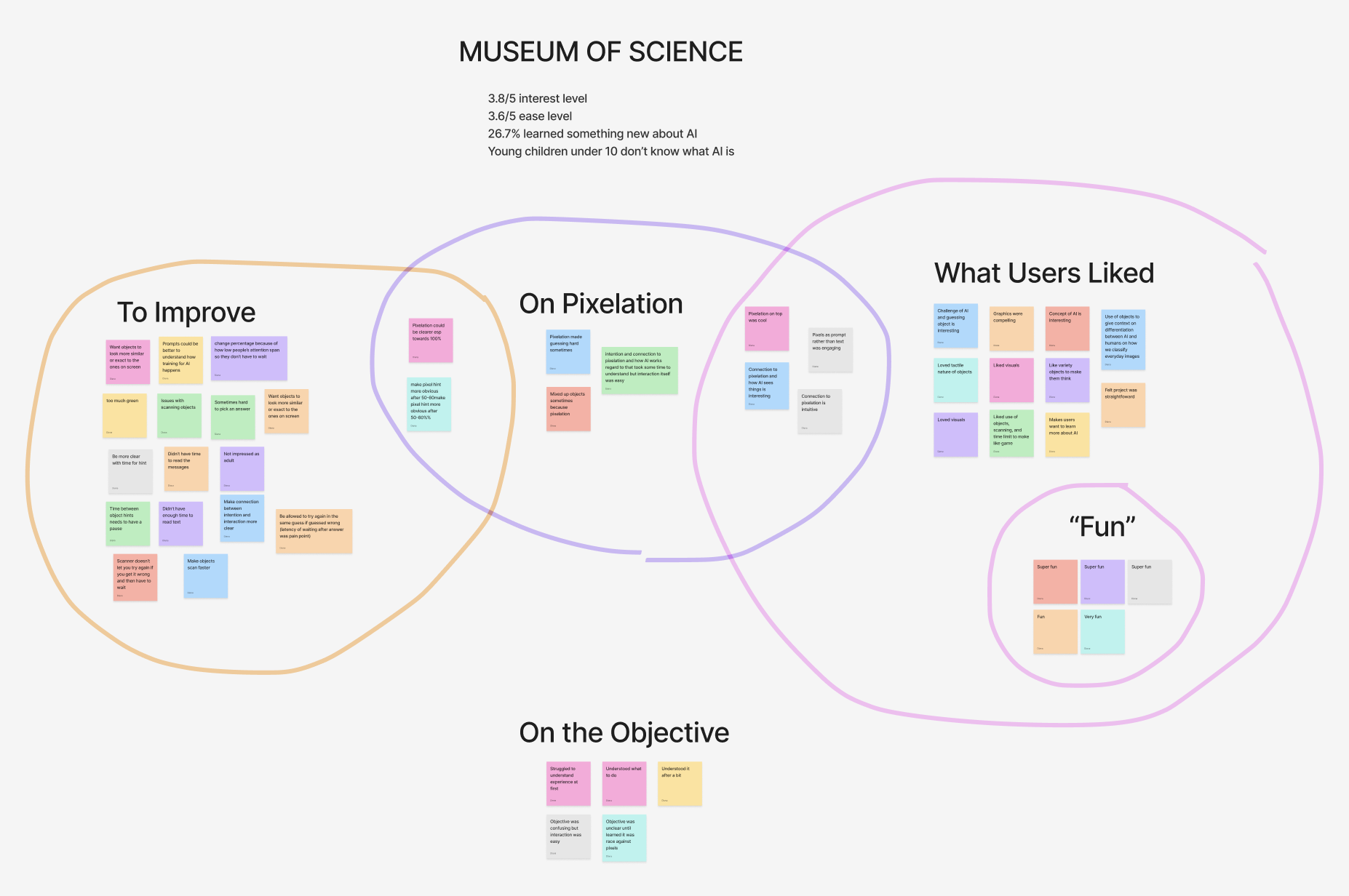

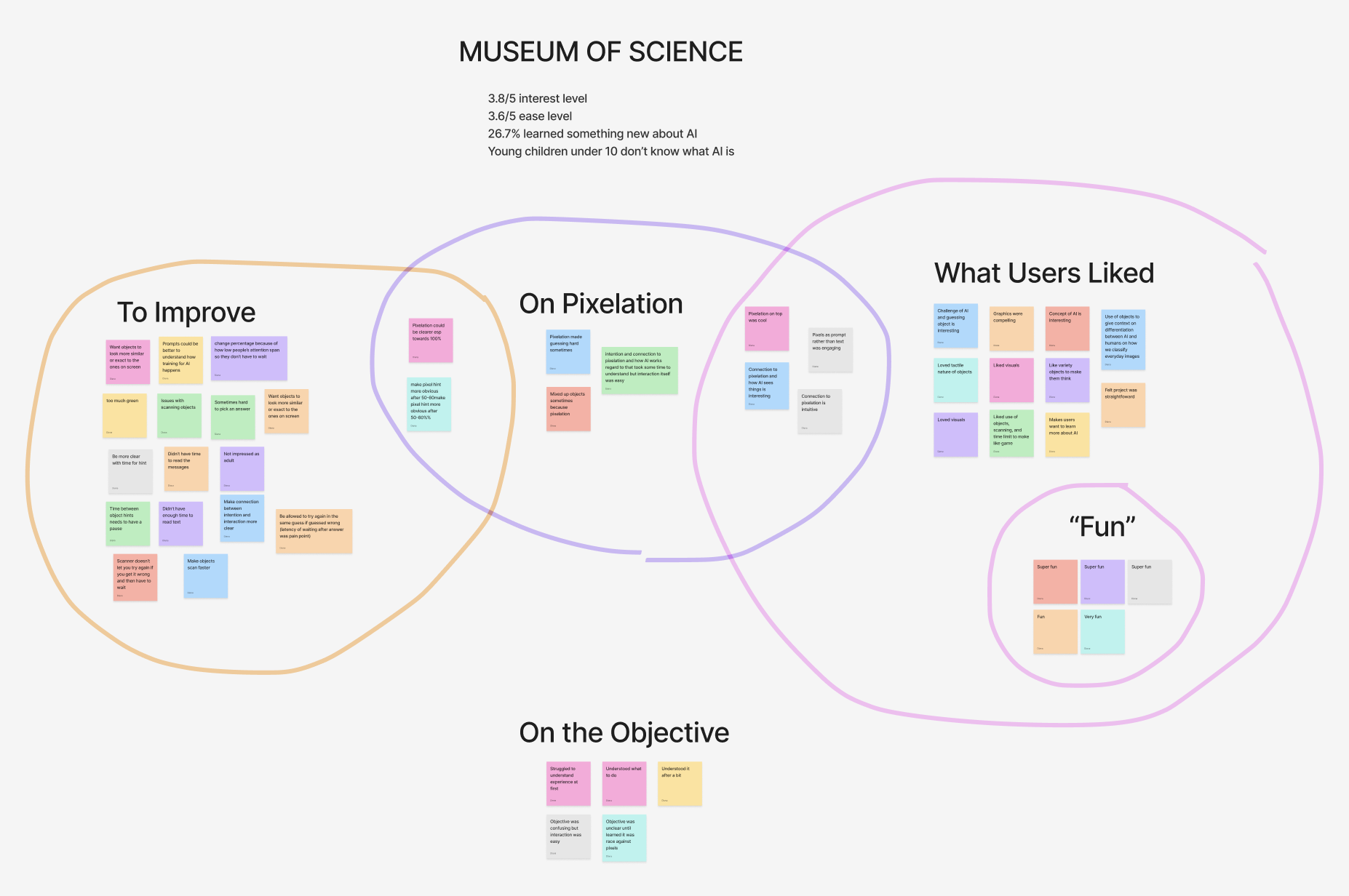

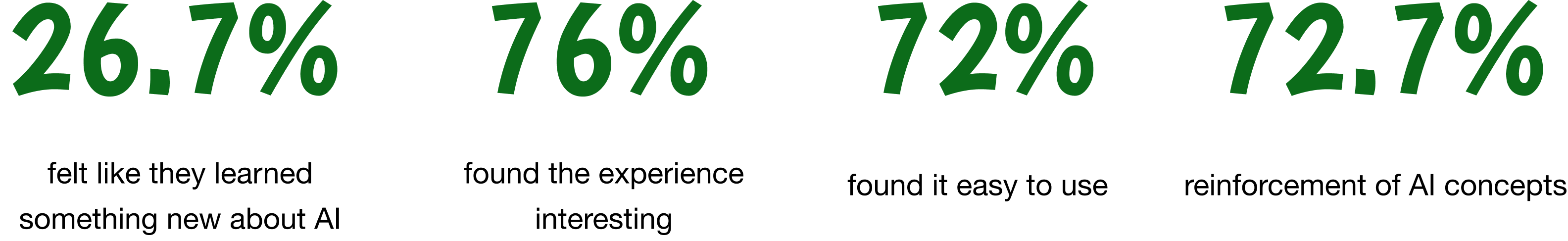

I conducted analysis on the findings by first grouping all the data by common category, of which I found four with overlapping area: areas to improve, comments on pixelation, what users liked, and remarks on the objective.

To my surprise, all young children under the age of 10 years old didn’t know what AI was. Although this eliminates the AI learning experience for that age group and younger, it could prompt at-home conversations between children and their parents about AI and in the meantime, the experience can act as a simple trail camera guessing game that could still be educational in its own right.

Recommendations and Reflections

Looking forward into the future of FAST table technology experiences.

Users overall enjoyed the experience. The visual prompts rather than written prompts should be maintained as they are engaging and resonate with users. The level of pixelation also hits our goal of “productive struggle”, as users couldn’t immediately figure out what the object was (only 2/9 comments on pixelation viewed it as detrimental to the project).

A lot of the feedback on what to improve was surrounding a disconnect between the designs presented to development and what development gave as a final output. Regardless, it’s important insight as to what’s valuable for users during the experience:

- The table should have a built-in label for the puck scanner so object placement is clearer to users

- Users need time to read the system feedback messages and the time between object hints needs a pause

- It’s important to make it clear whether users can select a second object before the time runs out or not

- Since a lot of the museum’s demographic is a lot younger (and therefore, shorter), they either don’t know how to read or can’t see the top of the table, so written text on the screen should be read aloud by the system to be more inclusive

The biggest thank you to the Museum of Science for this opportunity and specifically to Rachel Fyler, Sunewan Paneto, Bobbie Oakley, Ben Wilson, Dorian Juncewicz, Meg Rosenburg, Becki Kipling, Tim Porter, and Chris Brown for their guidance. I am so honored to have had this experience!

Diana Chalakova

About

Through AI’s Eyes

The Museum of Science in Boston partnered with the Parsons School of Design in a collaborative course on rapid prototyping for interaction design. I led my team of four in concept ideation, research, info architecture, and prototyping while constantly meeting with the stakeholders and our developer before I led usability testing on the functional high-fidelity prototype in the museum.

Role

UX Design, Web Design, Research

Timeline

Aug – Dec 2025

(4 months)

Tools

Figma, FAST Table, Unity

Problem

How might we create and test a high-fidelity prototype that teaches museum visitors about a modern scientific revolution?

The Museum of Science in Boston partnered with the Parsons School of Design in a collaboration that was centered around using their new “Flexible, Accessible Strategies for Timely Digital Exhibit Design” (FAST) table technology. They wanted us to create a high-fidelity prototype and perform in-person usability testing with it to investigate whether they should continue with the technology.

Solution

An interactive game that puts the user in the role of AI identifying objects in a nature scene.

Instead of using verbal prompts, we have visual prompts as pixelated image that slowly become clearer. We wanted to lean into the concept of “productive struggle”, so the system presents a pixelation of one of the five objects and the user has to decide which corresponding object in the scene it is before 30 seconds are up by placing the respective 3D print on the detecting platform, as each object has a unique QR code that the system scans.

Our objective was that by playing, users would learn how hard it can be for AI to identify objects, as AI systems use patterns, colors, and shapes to make educated guesses about what they see. Just like humans, AI can get confused when objects look similar or when clues are vague. The broader message for adults would be about why training data is so important in machine learning. When AI misidentifies objects, it can affect real people – from self-driving cares mistaking shadows for obstacles to photo apps mislabeling faces.

Research

Using simple, unbiased, and objective shapes to test a complex process.

We started our ideation process using leaves as an unbiased and widely understood object. The user would be presented with 6 similar but still different objects, the system would give a very vague prompt, and the user would have to make a guess as to which object it’s referring to. If the user is right, it moves onto the next general prompt. If they are not, the system gives a slightly more specific prompt.

The following is a storyboard that I created to show our stakeholders at the museum what our concept was, which they were very excited about:

We used simple shapes to perform our playtesting with five participants. Participants were instructed to read the prompt and place their object of choice on top of the Apple computer’s logo. Most of them placed possible shapes on the side as a visual aid to help them narrow down their options. Everyone was able to guess the objects during the first two attempts. We discovered that we need to have clear instructions for removing previous objects and that participants fidgeted with blocks like Legos, so we need to make the final 3D print durable.

However, we realized that the written prompts were not centered enough around AI and there was a disconnect between AI object recognition and prompt engineering that was a gap in our concept. Stakeholders also wanted the objects to be all completely different from one another.

Ideation

Using storytelling and visual prompts to create an educational experience.

As a solution to the AI concept disconnect, I proposed that we give the user visual prompts rather than written prompts. This would be similar to how the game Cooking Mama by Square Enix presents to players a pixelated image that slowly depixelatates of the next ingredients that players need to pick before the image becomes clear..

To align with the stakeholder needs of the objects all being different, I proposed that we have the objects live in the same world so we can still tell a story with the experience. The world I suggested which we continue with was a forest scene with the user viewing it through a trail camera, with the objects being a deer, tree, flower, rock, and cabin. The following is the information architecture I created:

The rest of my teammates each respectively created the visuals assets, worked on the Unity development of it using the template the museum gave us, and created the 3D prints of the objects. I led the planning and creation of the high-fidelity wireframes in Figma for development to work with. I made sure that the camera details were minimal to not be distracting and the different components of the experience were labeled for user ease of understanding.

In the 30 second countdown, the image would come more into focus. The circles at the bottom represent the five different 3D printed objects. Despite the prompt being visual, we felt it was important to still have a written statement about the objective of the experience and connect it to AI.

When the user guesses it right, the object is highlighted in the scene by a green box. If they guess it wrong, it’s a red box. Either way, the explanation of how AI would think about it remains the same, going back to the guessing screen for the next object. The system cycles through them at random, with no end.

Usability Testing Results

Testing in the Museum of Science with the target audience.

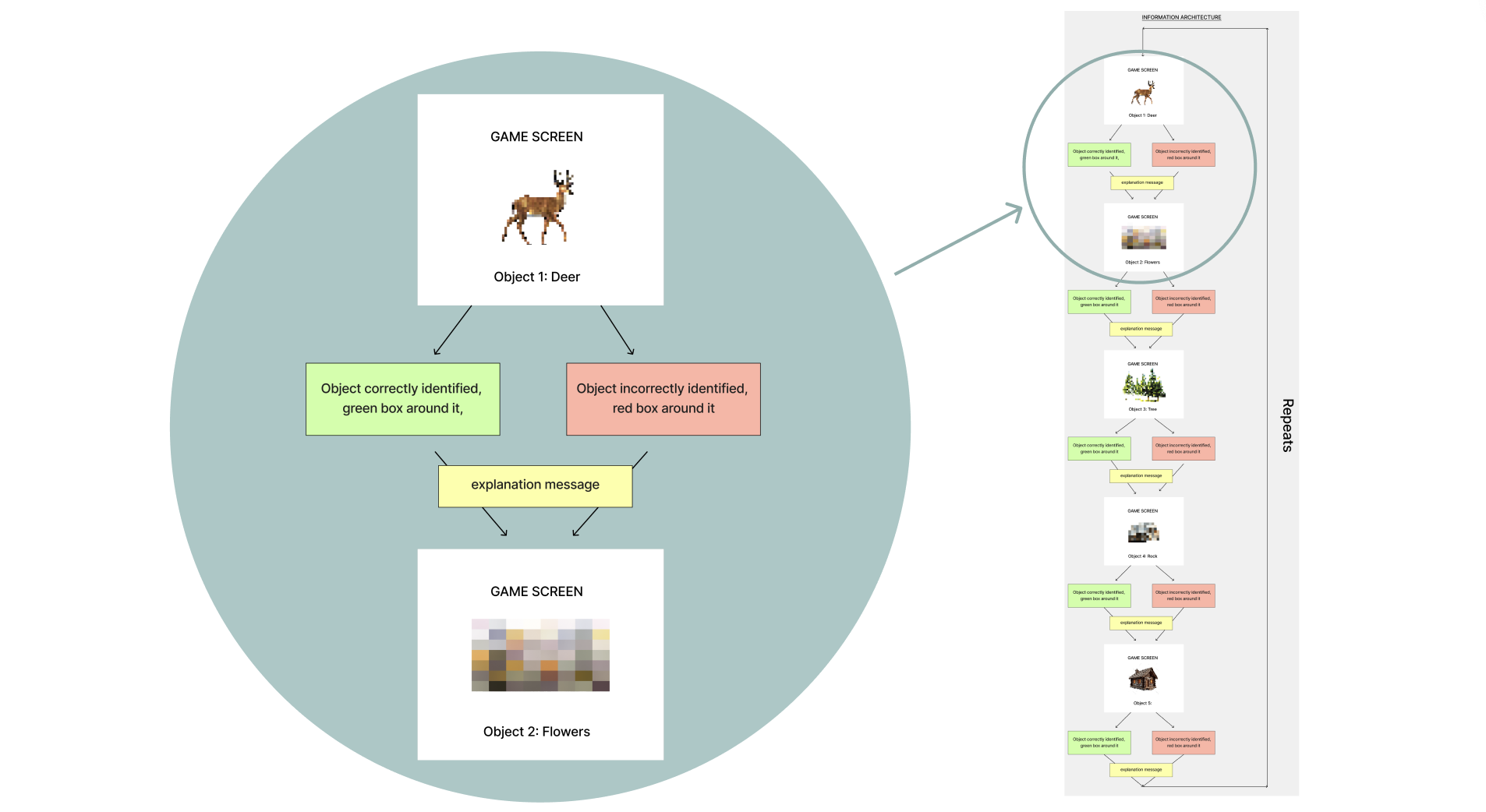

We tested our prototype with 15 users between ages 4 to 65. Data collection methods were focused on one-on-one interviews and observing behavior. We had a team member giving users an onboarding speech that informed them that we will not collect any identifiable characteristics, two team members observing user behavior and encouraging thinking out loud, and other performing post-experience interviews.

I conducted analysis on the findings by first grouping all the data by common category, of which I found four with overlapping area: areas to improve, comments on pixelation, what users liked, and remarks on the objective.

To my surprise, all young children under the age of 10 years old didn’t know what AI was. Although this eliminates the AI learning experience for that age group and younger, it could prompt at-home conversations between children and their parents about AI and in the meantime, the experience can act as a simple trail camera guessing game that could still be educational in its own right.

Recommendations and Reflections

Looking forward into the future of FAST table technology experiences.

Users overall enjoyed the experience. The visual prompts rather than written prompts should be maintained as they are engaging and resonate with users. The level of pixelation also hits our goal of “productive struggle”, as users couldn’t immediately figure out what the object was (only 2/9 comments on pixelation viewed it as detrimental to the project).

A lot of the feedback on what to improve was surrounding a disconnect between the designs presented to development and what development gave as a final output. Regardless, it’s important insight as to what’s valuable for users during the experience:

- The table should have a built-in label for the puck scanner so object placement is clearer to users

- Users need time to read the system feedback messages and the time between object hints needs a pause

- It’s important to make it clear whether users can select a second object before the time runs out or not

- Since a lot of the museum’s demographic is a lot younger (and therefore, shorter), they either don’t know how to read or can’t see the top of the table, so written text on the screen should be read aloud by the system to be more inclusive

The biggest thank you to the Museum of Science for this opportunity and specifically to Rachel Fyler, Sunewan Paneto, Bobbie Oakley, Ben Wilson, Dorian Juncewicz, Meg Rosenburg, Becki Kipling, Tim Porter, and Chris Brown for their guidance. I am so honored to have had this experience!

Diana Chalakova

About

Through AI’s Eyes

The Museum of Science in Boston partnered with the Parsons School of Design in a collaborative course on rapid prototyping for interaction design. I led my team of four in concept ideation, research, info architecture, and prototyping while constantly meeting with the stakeholders and our developer before I led usability testing on the functional high-fidelity prototype in the museum.

Role

UX Design, Web Design, Research

Timeline

Aug – Dec 2025

(4 months)

Tools

Figma, FAST Table, Unity

Problem

How might we create and test a high-fidelity prototype that teaches museum visitors about a modern scientific revolution?

The Museum of Science in Boston partnered with the Parsons School of Design in a collaboration that was centered around using their new “Flexible, Accessible Strategies for Timely Digital Exhibit Design” (FAST) table technology. They wanted us to create a high-fidelity prototype and perform in-person usability testing with it to investigate whether they should continue with the technology.

Solution

An interactive game that puts the user in the role of AI identifying objects in a nature scene.

Instead of using verbal prompts, we have visual prompts as pixelated image that slowly become clearer. We wanted to lean into the concept of “productive struggle”, so the system presents a pixelation of one of the five objects and the user has to decide which corresponding object in the scene it is before 30 seconds are up by placing the respective 3D print on the detecting platform, as each object has a unique QR code that the system scans.

Our objective was that by playing, users would learn how hard it can be for AI to identify objects, as AI systems use patterns, colors, and shapes to make educated guesses about what they see. Just like humans, AI can get confused when objects look similar or when clues are vague. The broader message for adults would be about why training data is so important in machine learning. When AI misidentifies objects, it can affect real people – from self-driving cares mistaking shadows for obstacles to photo apps mislabeling faces.

Research

Using simple, unbiased, and objective shapes to test a complex process.

We started our ideation process using leaves as an unbiased and widely understood object. The user would be presented with 6 similar but still different objects, the system would give a very vague prompt, and the user would have to make a guess as to which object it’s referring to. If the user is right, it moves onto the next general prompt. If they are not, the system gives a slightly more specific prompt.

The following is a storyboard that I created to show our stakeholders at the museum what our concept was, which they were very excited about:

We used simple shapes to perform our playtesting with five participants. Participants were instructed to read the prompt and place their object of choice on top of the Apple computer’s logo. Most of them placed possible shapes on the side as a visual aid to help them narrow down their options. Everyone was able to guess the objects during the first two attempts. We discovered that we need to have clear instructions for removing previous objects and that participants fidgeted with blocks like Legos, so we need to make the final 3D print durable.

However, we realized that the written prompts were not centered enough around AI and there was a disconnect between AI object recognition and prompt engineering that was a gap in our concept. Stakeholders also wanted the objects to be all completely different from one another.

Ideation

Using storytelling and visual prompts to create an educational experience.

As a solution to the AI concept disconnect, I proposed that we give the user visual prompts rather than written prompts. This would be similar to how the game Cooking Mama by Square Enix presents to players a pixelated image that slowly depixelatates of the next ingredients that players need to pick before the image becomes clear..

To align with the stakeholder needs of the objects all being different, I proposed that we have the objects live in the same world so we can still tell a story with the experience. The world I suggested which we continue with was a forest scene with the user viewing it through a trail camera, with the objects being a deer, tree, flower, rock, and cabin. The following is the information architecture I created:

The rest of my teammates each respectively created the visuals assets, worked on the Unity development of it using the template the museum gave us, and created the 3D prints of the objects. I led the planning and creation of the high-fidelity wireframes in Figma for development to work with. I made sure that the camera details were minimal to not be distracting and the different components of the experience were labeled for user ease of understanding.

In the 30 second countdown, the image would come more into focus. The circles at the bottom represent the five different 3D printed objects. Despite the prompt being visual, we felt it was important to still have a written statement about the objective of the experience and connect it to AI.

When the user guesses it right, the object is highlighted in the scene by a green box. If they guess it wrong, it’s a red box. Either way, the explanation of how AI would think about it remains the same, going back to the guessing screen for the next object. The system cycles through them at random, with no end.

Usability Testing Results

Testing in the Museum of Science with the target audience.

We tested our prototype with 15 users between ages 4 to 65. Data collection methods were focused on one-on-one interviews and observing behavior. We had a team member giving users an onboarding speech that informed them that we will not collect any identifiable characteristics, two team members observing user behavior and encouraging thinking out loud, and other performing post-experience interviews.

I conducted analysis on the findings by first grouping all the data by common category, of which I found four with overlapping area: areas to improve, comments on pixelation, what users liked, and remarks on the objective.

To my surprise, all young children under the age of 10 years old didn’t know what AI was. Although this eliminates the AI learning experience for that age group and younger, it could prompt at-home conversations between children and their parents about AI and in the meantime, the experience can act as a simple trail camera guessing game that could still be educational in its own right.

Recommendations and Reflections

Looking forward into the future of FAST table technology experiences.

Users overall enjoyed the experience. The visual prompts rather than written prompts should be maintained as they are engaging and resonate with users. The level of pixelation also hits our goal of “productive struggle”, as users couldn’t immediately figure out what the object was (only 2/9 comments on pixelation viewed it as detrimental to the project).

A lot of the feedback on what to improve was surrounding a disconnect between the designs presented to development and what development gave as a final output. Regardless, it’s important insight as to what’s valuable for users during the experience:

- The table should have a built-in label for the puck scanner so object placement is clearer to users

- Users need time to read the system feedback messages and the time between object hints needs a pause

- It’s important to make it clear whether users can select a second object before the time runs out or not

- Since a lot of the museum’s demographic is a lot younger (and therefore, shorter), they either don’t know how to read or can’t see the top of the table, so written text on the screen should be read aloud by the system to be more inclusive

The biggest thank you to the Museum of Science for this opportunity and specifically to Rachel Fyler, Sunewan Paneto, Bobbie Oakley, Ben Wilson, Dorian Juncewicz, Meg Rosenburg, Becki Kipling, Tim Porter, and Chris Brown for their guidance. I am so honored to have had this experience!